Breaker Morant, along with Gallipoli, is one of the most important Australian films which supported national identity-making. The former incorporates the colonial betrayal, while the latter pictures colonial loyalty. The common theme of anti-colonialism juxtaposes the two films. Breaker Morant portrays the dark side of imperialism and the devastating power of the coloniser, which even concerns the colonial auxiliaries. Gallipoli relies more on the audience’s contribution to answer the question whether the protagonist, Archy, had ever stood a chance and what the whole sacrifice was made for. Colonialism is, therefore, represented as an abnormal situation where heroes can only die, but they are bested by the impossibility of survival at least.

Both films were made roughly at the end of the era of decolonisation, which took place not only outside of Australia, but also within Australian culture in the sense that the cultural cringe seemed to decline after a range of ‘made-in-Australia’ cultural novelties, such as the Sydney Opera House and the first Australian Nobel Prize winner, Patrick White, which all contributed to the decline of Britain as a cultural point of reference. As the power of the coloniser gradually abated in Australian culture, it is not surprising that colonialism was not portrayed in favour of Britain, such as in Breaker Morant. Instead, the crude bitterness of imperial reality is contrasted with the subjugated auxiliary, yet heroic, role of the colonised. As a result, Breaker Morant supports the historical agenda of decolonisation on the mental level too.

Consequently, the film constructs an anti-colonial sentiment while illuminating the heroism of the subsidiary. This statement is modified to ‘the film creates a national myth by making heroes of villains who were not better than their masters’, as the critics could be summarised. This is discussed below, but it is essential to conjure up here that Australian nationalist discourse is often exposed to attack by its very basis, namely if Australians have ever been worth any national pride ever since their convict past made them inferior in the jingoistic British discourse, which was preserved throughout Australian history in the bushranger heritage, the ‘cannon-fodder’ way of deploying diggers at Gallipoli, and in Breaker Morant as well. In the latter, an Australian has to be rigidly sentenced since they follow their national habit of unregulated bushy battler lifestyle in the veldt, even if the Australian soldiers are actually following orders. The logic is simple: if the crime is committed by the British high command through orders, it is tolerated and not punished; if the colonial soldier executes the order, he is immediately identified with the usual stereotype of a sinful convict or bushranger type of character who is not only worthy of his ancestry, but also deserves the punishment by the moral guider, i.e. the coloniser. Unanimously, the present-day discourse ponders over the same question, but with the difference that now it is the real Breaker Morant who is questioned if he was worthy of a hero or a protagonist in a film at all; meanwhile, the British colonisers are, as a rule, rewarded with excuse. Indirectly, the nationality of Australians thus is severely attacked by suggesting that this type of the Australian character cannot be recognised as a hero; every attempt at making heroes is an act of making myth; by extension, making a nation or national identity out of a colonial people, i.e. Australians, is not more than making an ‘imagined community’, with some references to Benedict Anderson’s work too.

The reason why Breaker Morant is seen as reality, but criticised for being inaccurate in terms of reality (e.g., Henry 9) is a difficult question. It could be the need for heroes, the anti-colonial or postcolonial sentiment, and the national pride which promote the desire to accept the story of Breaker Morant more or less as it is. That is, there is no explicit connection between any supposed attempt of creating a national myth or a fake identity by the film and that the film is seen as reality, which thus receives criticism about inaccuracies. In this way, there is no national propagandistic quality of Breaker Morant despite that the customary critical practice prefers discrediting national discourse arguing that it uses propaganda for nation-making.

Breaker Morant

The gist of the film and the real story is the same: colonial subjugation of nationality, acting with fortitude and self-confidence even in abnormal situations, and that the real criminal is hiding in the background. While these are being discussed, it is demonstrated that the film did have a reason to portray the events in its way without distorting how reality had been conceived. First, the colonial subjugation of nationality is related to the Federation in 1901. That occurred amidst the Second Boer War, the first war of Australia as a virtual nation after obtaining the status of Dominions. The lesson of the entire conflict was also that Australia’s postcolonial involvement in an imperialist war was done with an auxiliary role, but Australians were treated as subservient colonial people who were still under the control of the British power. The proof is provided by the fact that British generals simply described Australian soldiers as “white livered curs” and the execution of ‘Breaker’ Morant and Handcock by the British occurred prior to any notification of the Australian government or the public (Rickard 114). Besides, “The double standards being applied in the case are revealed late in the film, when Captain Taylor, also accused of killing prisoners, informs his co-prisoners that he will be spared as he is a British intelligence officer and thus valuable, whereas Morant and the other Australians ‘won’t be missed’” (“‘Breaker’ Morant”). These are themselves enough to illustrate that the British and Australians were not equal partners and Australians were seen merely as convicts to their past. Nationhood lacked any respect or recognition by the British. Critics agree that “Australia had not shaken off its colonial oppression... we still suffered from a national inferiority complex” and “Resentment over this apparent willingness to play a subservient role in foreign wars in turn fuelled growing Australian nationalism” (“‘Breaker’ Morant”). There were controversies even at the time of the imperialist era:

The incident had sparked enormous controversy at the time, with further interest being created when one of the accused, George Witton, published a polemical account of the trial in his 1907 book Scapegoats of Empire. Witton argued that the three accused Australian officers were convenient scapegoats to take the blame for the widespread war crimes that took place during the latter part of the war. He further alleged that their trial and punishment helped to cover up the fact that Lord Kitchener himself had approved the policy of shooting Boer prisoners, and also encouraged the Boers to make peace with the British authorities (Witton, 1907, n.p.). There have been suggestions that the distribution of Witton’s work was deliberately suppressed by the Australian government, although another explanation is that a major fire at the publisher’s warehouse destroyed much of the stock and made surviving copies rare (“‘Breaker’ Morant”).

The film also includes the theme “morally indefensible behaviour” (“‘Breaker’ Morant”). While the paradoxical nature of Australian nationalism resulted in fighting for the British Empire with a sense of “blood and cultural ties” (Henry 2), the true realisation of Australian nationality occurred when, ultimately, the moral issues and methods of the war were in the focus of criticism. The film portrays this moral level, and the story of Morant is also about this, but with a focus on the crimes committed by the auxiliary manpower. Relocating the moral focus to the coloniser is a remunerative approach since this war was the war of British imperialism and the orders were given by the British high command, which was also an argument for the accused. While most critics tend to insist upon the discrepancies between the film and the real Morant, and so does Adam Henry in his article “Australian Nationalism and the Lost Lessons of the Boer War” to some extent, there is still a cautious attempt of balancing in Henry’s account even if he does not scrutinise the high command enough:

Oddly though, the legend of Morant within Australian nationalism is framed squarely within the discourse of a victim - a victim of Lord Kitchener, who represents perfidious Albion. Equally naïve are those that have defended Lord Kitchener and use these events to elevate Kitchener to quintessential gentleman-soldier pretensions. They argue that he oversaw a necessary and honourable prosecution of individuals guilty of murder. Therefore, by this logic, he was an honourable and moral military commander. This conveniently absolves him of any “criminal” guilt for the thousands of women and children who perished in unsanitary concentration camps (Henry 9).

As for this ‘moral’ and ‘honourable’ military commander, Lord Kitchener as a ‘gentleman-soldier’ had committed a series of disgraceful actions, which long has been part of the shame of British imperialism which is still not scrutinised enough in any British academic work or even in Breaker Morant.

On the contrary, Lord Kitchener is celebrated as a hero even today at the disgust of a Scottish newspaper which calls Kitchener a war criminal and claims, “To those in London who are organising this year of commemoration of the First World War, Horatio Kitchener is a war hero. To my mind he is a war criminal [Signed by a range of people.]” (Clayton et al.). Indeed, Lord Kitchener’s ‘honourable’ deeds exceeded such a great amount that an entire website was needed to be dedicated just for enumerating the war crimes of Kitchener. It is a pity that these are not illuminated instead of the narrow-minded debate over what the real Morant and the legendary one committed or not. Henry agrees with this failure by conclusion (23). The website which deals with Kitchener claims that he was a war criminal. It refers to that the Hague Convention of 1907, the ‘UN of that time’, internationally condemned Kitchener’s method of warfare. Furthermore, Kitchener has been said to have led a “war to liberate the black population” and the Uitlanders (“About us”, see at “The Crimes”).

As for the Uitlanders, who were British immigrants to the diamond and goldfields of the Boer states, they did not receive any improvement after the British victory despite that Joseph Chamberlain, Secretary of State for the Colonies, insisted on granting rights for them as a casus belli (“About us” and Búr 12). As for the liberation of the black population, the importance of the natives of Africa for the British was well-demonstrated by the fact that the British troops burned the kraals of the blacks who then had to move in black concentration camps where they were exploited as labour force for military supply. By May 1902, 66 black concentration camps had a total number of approx. 115,000 blacks, most of whom were women and children (Pretorius 102-104). The number of those blacks who died in the camps is unknown “as the British army did not regard them as important enough to keep records” (Clayton et al.).

Kitchener had a leading role in waging the war with scorched earth policy, which resulted in massacring livestock, even where it was needless, and destroying 30,000 houses, just what was admitted by the British (Pretorius 104). It was Kitchener who completed a whole system of deportation of the homeless Boer women and children to 34 concentration camps. Chamberlain argued that this was done for humane purposes despite the fact that the Boer soldiers who surrendered received better supply than the women and children, who were called ‘undesirables’ (Pretorius 105). Ca. 110,000 Boers, i.e. about one sixth of the total Boer population, were deported and 27,927 died in the camps, of whom 26,251 were women and children and more than 22,000 children were under the age 16 (Pretorius 105). Kitchener himself deliberately distorted the reality of the camps and misinformed the British Parliament with reports about “sufficient allowance” and that the women and children are “satisfied and comfortable” (“Parliamentary Debates...”).

When Emily Hobhouse revealed the disastrous conditions of the camps to the public, Kitchener called her “that bloody woman” (Morgan 3). Cornelis Broeksma, a Dutchman, was even arrested and executed on the demand of Kitchener because he wanted to inform the public about the camps (“Executed...”). Lloyd George, who later became PM, condemned Kitchener’s methods and accused him of a policy of extermination; “The Herod of old sought to crush a little race by killing all the young children. It was not a success, and he would commend that story to Herod’s modern imitator” (Pearce). Next, The Bulletin called Kitchener the real villain while Morant a hero (Wilcox). Again, Kitchener contributed to the racial hatred in South Africa and a “BBC documentary programme revealed that he told blatant lies over scandalous practices during the war” (“Kitchener’s contribution...”).

Yet the uttermost scandal Kitchener ever did had been already done by the time of the Second Boer War. One year preceding the Anglo-Boer conflict, in 1898, the Battle of Omdurman, or the Massacre of Omdurman, took place in the Sudan between the British and Egyptian combined troops led by Kitchener and the Mahdist forces of the Sudan. The aftermath was devastating as Sven Lindqvist, a Swedish historian, revealed this disgraceful episode of colonialism:

[The battle] was fought in the name of civilisation, but nobody in Europe asked how it came about that 15,000 Sudanese were killed while the British lost only 48 men. Nor did anyone question why almost none of the 16,000 Sudanese wounded survived. In “Exterminate All the Brutes”, Lindqvist turns up 19th-century newspaper accounts of British massacres of wounded Sudanese after the battle (“The Crimes”).

Sir Winston Churchill, who was a war-correspondent at that time in Africa, contended that Kitchener was personally responsible for these crimes: “I shall merely say that the victory at Omdurman was disgraced by the inhuman slaughter of the wounded and that Kitchener was responsible for this” (Daly 3-4). As for the imperialist jingoism, which was for spreading civilisation in Africa for the ‘brutes’, the future PM Campbell-Bannerman said the following with regard to the Boer War and Kitchener: “When is a war not a war? When it is waged in South Africa by methods of barbarism” (“Articles”, see at “The Crimes”). The barbarism of the colonisers manifested itself after the Massacre of Omdurman too: rape and looting were committed by the British soldiers, which Kitchener did not even attempt to stop; on the contrary, he “personally authorized defiling the Mahdi’s Tomb” (North, in “The Sudan”).

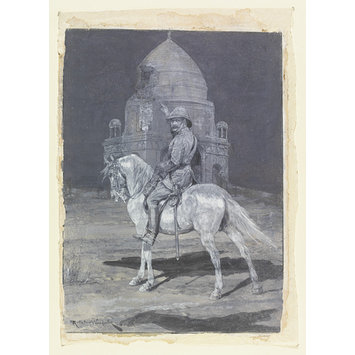

Kitchener ordered that the Mahdi’s bones be cast into the Nile, which caused utter outrage in Britain, though Kitchener’s activity was fully backed by British officials (Warburg 6). Only the acting consul-general refused one of Kitchener’s orders of execution arguing that it would cause a serious anger of the public opinion in England (Warburg 6). Not only the Mahdi’s bones, but also the mosque and the sacred place of pilgrimage were desecrated with the dome being a “particular target” (Daly 5) of bombardment. The Tomb was ultimately blown up (Daly 5). Kitchener continued his barbarism with that he humiliated the memory of the Mahdi by using the Mahdi’s skull, which was the only remaining object of him, as a trophy. He played with the idea of using the skull as an inkstand or a drinking-cup and displayed it on his desk for this purpose (Daly 6 and North, in “The Sudan”). On top of these, “Kitchener later tried to deflect the criticism by pleading his absence en route to Fashoda...” (Daly 6). Churchill wrote about this too: “By Sir H. Kitchener’s orders, the Tomb has been profaned and razed to the ground. The corpse of the Mahdi was dug up. The head was separated from the body, and, to quote the official explanation, ‘preserved for future disposal’...” (“Articles”, see at “The Crimes”). Figure 1 shows a painting of Kitchener and this memorable moment at Omdurman titled Lord Kitchener on horseback, pointing at the Mahdi’s tomb at Omdurman, at night.

Figure 1: Lord Kitchener on horseback, pointing at the Mahdi’s tomb at Omdurman, at night

After the discussion of some of Kitchener’s crimes, one can propose the question why it is Morant’s issue that received punishment and still receives critiques, even if he committed those crimes. It was not a myth-making, after all, that the British High Command had to find scapegoats (Gardner 27) to demonstrate that war crimes were punished. Subsidiary Australian soldiers were good scapegoats because thus the British public opinion would not rage over the execution of British soldiers and the morale of the British troops, which was horrendous during the Boer War, and even Kitchener could be seen as a gentleman-soldier who made justice within his army too. The betrayal of low-ranking soldiers and their scapegoating are related to the Vietnam War too, which was also part of the inspiration of some adaptations of the Morant story (“‘Breaker’ Morant”). The 1982 American film First Blood portrays a similar case of betrayal and scapegoating, related to the Vietnam War, in a particularly emotional scene at the end:

Rambo: Nothing is over! Nothing! You just don’t turn it off! It wasn’t my war! You asked me I didn’t ask you, and I did what I had to do to win, but somebody wouldn’t let us win! Then I come back to the world, and I see all those maggots at the airport, protestin’ me and spittin’, callin’ me baby killer and all kinds of vile crap! Who are they to protest me?! Huh?! Who are they?! Unless they been me and been there and know what the hell they yellin’ about! (First Blood)

Not unlike First Blood, Breaker Morant evokes the conditions in the Boer War and appeals to the overwhelming effect of pressure: “The tragedy is that these horrors are committed by normal men in abnormal conditions” (Breaker Morant).

In consequence, Breaker Morant is not a nationalist myth since it is about an understandable representation of what the Boer War was all about from the perspective of the subservient; it reflects the anti-imperialist and anti-British sentiment of the then-contemporary critics, which were and would be understandable if Kitchener had not been exonerated and worshipped annually and the contemporary critics had scrutinised the dark side of the high command too. In this way, the real Morant took the blame and the major criminals successfully avoided the punishment. Thus the film is about the reality of how colonial ties were seen as and why it is necessary to be conscious about colonial relations and nationality. Criticising Breaker Morant for what the real Morant was like is not unlike an allusion for that the Australian nationalist sentiment is guilty of not admitting the criminal, or convict, past and creating unjustified nationality.

References

“‘Breaker’ Morant.” Colonial Film––Moving Images of the British Empire. Colonial Film. Web. 6 May 2015. <http://www.colonialfilm.org.uk/node/1128>.

Búr, Gábor. Az apartheid születése: A gyarmati önkormányzat visszaállítása Dél-Afrikában, 1906-1907. L’Harmattan, 2010. Print.

Clayton, Alan, et al. “Kitchener Was a War Criminal.” Herald Scotland. The Herald, 15 Jan. 2014. Web. 12 May 2015. <http://www.heraldscotland.com/comment/letters/kitchener-was-a-war-criminal.23179113>.

Daly, M. W. Empire on the Nile: The Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, 1898-1934. First ed. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2003. Print.

“Executed for Exposing the Truth.” Lord Horatio Kitchener––War Criminal. Angloboer.com. Web. 13 May 2015. <http://angloboer.com/artbroeksema.htm>.

Gardner, Susan. “Can You Imagine Anything More Australian?: Bruce Beresford’s Breaker Morant.” Kunapipi 3.1 (1981): 25-41. University of Wollongong. Web. 6 May 2015. <http://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1094&context=kunapipi>.

Henry, Adam. “Australian Nationalism and the Lost Lessons of the Boer War.” Australian War Memorial. Web. 6 May 2015. <https://www.awm.gov.au/journal/j34/boer.asp>.

“Kitchener’s contribution to racial hatred.” Lord Horatio Kitchener––War Criminal. Angloboer.com. Web. 13 May 2015. <http://angloboer.com/arthatred.htm>.

Morgan, Kenneth O. “The Boer War and the Media (1899-1902).” Twentieth Century British History. 13. 1 (2002): 1-16.

Nagy, Robin. The Dark Side of the British Empire: The Second Boer War and Its Concentration Camps. LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing, 2014.

North, Don. “The Sudan.” Inappropriate Conduct: Mystery of a Disgraced War Correspondent. First ed. Bloomington: iUniverse, 2013. Print.

“Parliamentary Debates, 1901, XC: March 1, 179-80.” Stanford University. Accessed April 2, 2013. <http://www-sul.stanford.edu/depts/ssrg/africa/hansxc2.html>.

Pearce, Mike. Against the Empire: The Boer War. Last on Sat 25 Sep 1999. BBC. 1999. <http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p00lmqb5>.

Pretorius, Fransjohan. The A to Z of the Anglo-Boer War. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 2009. Print.

Rickard, John. Australia: A Cultural History. Web. 6 Dec 2013. <http://seas3.elte.hu/coursematerial/GallCecilia/Loyalties.PDF>.

“The Crimes.” Lord Horatio Kitchener––War Criminal. Angloboer.com. Web. 6 May 2015. <http://angloboer.com/crimes.htm>.

Warburg, Gabriel. “The Governor-General, Kitchener and Wingate.” Sudan Under Wingate: Administration in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan (1899-1916). First ed. Abingdon: Frank Cass and Limited, 1971. Print.

Wilcox, Craig. “Ned Kelly in Khaki?” Lord Horatio Kitchener––War Criminal. Angloboer.com. Web. 13 May 2015. <http://angloboer.com/artbreaker.htm>.

List of Figures

Figure 1. Woodville, Richard Caton. Lord Kitchener on horseback, pointing at the Mahdi’s tomb at Omdurman, at night. Ca. 1899, painted. Accessed at <http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O153532/lord-kitchener-on-horseback-pointing-watercolour-woodville-richard-caton/>.